Dead Pool at Lake Mead: Misconceptions and Myths

Just in case you've been living under a rock for the last several years, the Colorado River basin is in the midst of the worst drought in at least a millenium and a half, and the water levels in Lake Mead have been dropping to record lows. There's speculation that the reservoir might soon reach "dead pool", the point at which water can no longer flow out of the lake, and a lot of local residents are convinced that their taps will soon run dry. That leads me to write this post, busting some of the myths around the lake, the river, and the water that keeps our city alive.

1. Las Vegas is draining the Colorado dry

Many people look at Las Vegas, sitting as close as we do to Lake Mead and depending almost exclusively on its waters, as the main culprit in the draining of the Colorado River. It makes sense: our city is known for extravagance, the fountains of the Bellagio being an iconic image of the Strip, and it's easy to see the water intakes in the lake itself and presume that it's being drained by locals and tourists. That said, it's inaccurate.

The Colorado River Compact, the main agreement governing the allocation of the river's waters, gives the vast majority of them to California and Arizona. Of the 7.5 million acre-feet allocated to the lower basin states of California, Arizona, and Nevada, only 300,000 acre-feet are given to Nevada. California is allocated nearly 4.4 million, and actually uses over 5.2 million, exceeding their annual allocation by more than all the river water used in Nevada.

On top of that, Las Vegas has some of the most stringent water use regulations in the country, far stricter than in southern California. Those Bellagio fountains are brackish groundwater unsuitable for drinking, and reclaimed water is used to irrigate city parks and (ugh) golf courses in the region. Basically all water used indoors in the Valley is recycled and returned to the lake. And the outdoor water use that represents all of the water that we ultimately actually consume is becoming more strictly controlled, with bans on lawns in new construction and commercial and institutional spaces. The result of all of this is that, in 2018, even before recent shortage measures took effect, Las Vegas used only 243,000 acre-feet of water, and usage is expected to continue to decline.

2. Population growth is responsible for the dwindling Colorado

Perhaps, in a roundabout way, it is, but urban areas in general don't use the lion's share of the river's water. Rather, between 70 and 80% of the water is used for irrigation, permitting farming in the central Arizona desert and California's dusty Imperial Valley. This region produces nearly all of our nation's winter vegetables, but the single largest use of this water is for cattle feed. When you consider that beef production is also responsible for massive amounts of greenhouse gases, which are in turn worsening the drought, it seems like this is not the best use of our scarce and dwindling water resources.

The solution is to shift vegetable production to areas with less water stress (for example, the eastern half of the country, where climate change is driving increased precipitation and flooding) and to shift our diets away from beef, not to stop building housing in our tent-covered Southwestern cities.

3. Las Vegas is in danger of running out of water

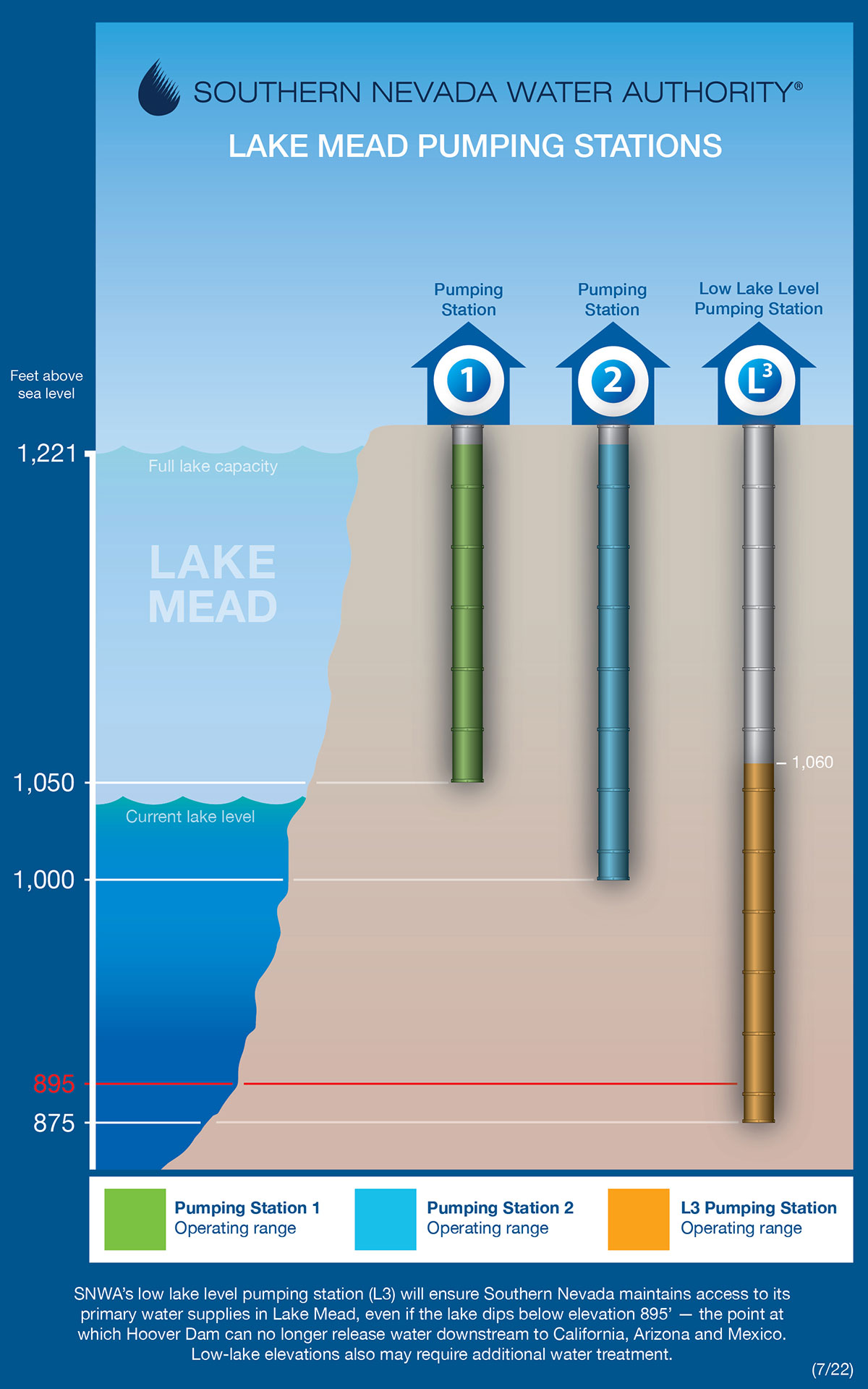

Las Vegas, however, draws its water from inside Lake Mead-- we're actually the only major river user to do so. You may have heard that one of the city's water intake valves was recently exposed by the receding water. Fortunately, that one hasn't been in use in 7 years. Water managers in Las Vegas completed a second, lower intake in the late 1990s, and a further, even lower one in 2020. Essentially a bathtub drain at the bottom of the lake, Intake 3 and its associated Low Lake Level Pumping Station can deliver water to Valley customers with the lake surface at an astonishingly low 875' (266m) above sea level, 20 feet below dead pool. That raises the question, of course, of what we do if it falls below that level? Well, read on.

4. Lake Mead at dead pool mostly affects Las Vegas

The biggest users of Colorado river water are California and Arizona, the former using more than twice as much as the latter. Water from the Colorado reaches California via the Colorado River Aqueduct, which begins at the southern end of Lake Havasu. Just on the other side of the Parker Dam from there is the main intake for the Central Arizona Project, the Mark Wilmer Pumping Plant. Both are, notably, downstream from Lake Mead. That is to say that, if Lake Mead reaches dead pool, Las Vegas will be able to draw water, but California and Arizona, the river's two biggest users, will not. 52% of Los Angeles' drinking water will be unavailable; Phoenix will lose 40%, Tucson nearly all (though they may be in a position to compensate with groundwater, for a time). Of course, the agricultural areas that rely on this water would be similarly unable to draw it, meaning this would also impact the diets of nearly all of North America, driving both vegetable and meat prices even higher than they already are.

There is also the issue of hydroelectric generation, which many also erroneously assume will primarily impact Las Vegas. In fact, Nevada gets only about a fifth of the power from the dam, with the bulk of it going to California. In a truly cosmic irony, the single largest power allocation from Hoover Dam goes to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, power that is then used to pump the very same water that generated it through the Colorado River Aqueduct. Hydro generation at Hoover Dam, which is already being curtailed due to low water levels, will primarily be replaced with fossil fuel generation in Las Vegas and southern California, and while Phoenix does have a nuclear plant, it is cooled from their wastewater treatment system, the water levels in which will no doubt be impacted by a drinking water shortage. The net result? More drought-prolonging CO2, a problem that affects us all.

Dead pool at Lake Mead would be a catastrophe, have no doubt. But Las Vegans will be in a much better position to weather that catastrophe than most of our desert neighbors, and that is going to come as an unpleasant surprise for Angelenos in particular.

5. Dead pool is a permanent condition

The good news is that, with the major river users unable to, well, use the river, suddenly Lake Mead would only be serving the demand in Las Vegas, which, as previously established, is a tiny fraction of the river's flow. The Colorado, even in drought, still averages between 9 and 10 million acre-feet of water flowing through its banks into the Lower Basin. If 10 million acre-feet are flowing into Lake Mead each year, and only 247,000 are flowing out, it's obvious that the reservoir will begin refilling. It would represent a serious disruption to the lives of millions who depend on river water, and a wake-up call for better management on the Colorado, as well as likely damage to the infrastructure of the dams, siphons, and pumps along the massive aqueducts that deliver the river's water to the thirsty cities and farms of the Lower Basin. It is, undoubtedly, a situation to avoid, which is why Bureau of Reclamation managers have instituted detailed drought management plans, with strict mandatory reductions that have already gone into partial effect, in order to avoid it. But it doesn't mean "we're out of water" for all time-- water will, eventually, flow past Hoover Dam once more.

And, when it does, hopefully we'll all be a little more aware of the complex systems that sustain our lives, and a little more judicious in their management.

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment